Collection Encounter: The London Archives

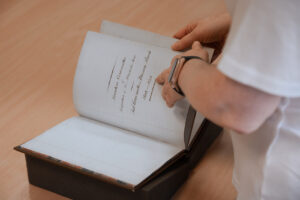

A photograph from the David Jacobs collection • Hidden Treasures/Jonathan Juniper

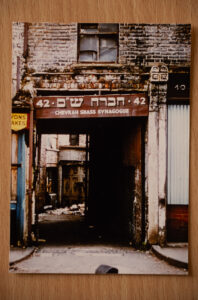

The entrance to The London Archives building • Hidden Treasures/Jonathan Juniper

The recently renamed The London Archives (formerly the London Metropolitan Archives) is the largest repository in the UK for archive material on Greater London and its environs and is funded and managed by the City of London Corporation.

Inside a former print works in Clerkenwell, there are millions of historical records housed on-site in two large buildings in vast temperature-controlled storage rooms with miles of shelving holding historic manuscripts, maps, photographs, books, films and many other items that explore the deep history of London from 1067 to the present day.

I have spent countless hours over the years in the wonderful reading room there looking at a wide range of material relating to Jewish communities across London and around the world, including the records of the former Sephardi community of Barbados, whose minute books are held at the London Archives (and belong to the UK’s Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation). I was excited to meet Nicola Avery, the archivist responsible for The London Archives’ Jewish collections, and see some of the treasures she had selected from their incredible collections.

We met Nicola at the front desk and she led us into the main exhibition space on the first floor, where a fascinating new exhibition on Lost Victorian London was on display. We visited the two fully accessible public rooms on the first floor where a large glass window separates the information area from the public Reading Room. The public can call up original material from the collections here if they have a History Card, which is freely available to anyone over 16. The large open-plan information area is where visitors can explore the catalogues, browse through the open access books and search online sites like Ancestry and Find My Past for free.

The Mediatheque facility allows researchers to view digitised images from the collections including the London Picture Archive, which holds most of The London Archives’ graphic and photograph collections. People can also watch archive films and listen to oral history recordings in the Mediatheque area including a project by Liberal Judaism, called Rainbow Jews, which records the stories of Jewish LGBT people in the UK.

As we walked up another flight of stairs to view the treasures Nicola had selected, we discussed the considerable range of Jewish material which is held in The London Archives. ‘Whether it’s photographs of the Jews’ Free School or minute books from synagogues, what I love is that you have so many synergies and links between the collections here,’ said Nicola as we entered a small book lined space. ‘There are links everywhere, you can explore both sides of stories here.’

Nicola has been working with the Jewish collections at the archives for over twenty years and told us the oldest Jewish material record The London Archives hold is a denisation document, a petition sent to Oliver Cromwell in 1656 from the Spanish and Portuguese community. ‘Our collections span all the Jewish traditions,’ said Nicola, ‘from Sephardi, to Orthodox, Reform, Liberal and Progressive. We also hold the records of the United Synagogue, the Federation of Synagogues and individual synagogue collections as well as the records of the Board of Deputies. We worked closely with Charles Tucker, the honorary record keeper at the United Synagogue back in the 1980s, who was keen that Jewish material should stay in London particularly the large organisations like the United Synagogue, the Board of Deputies, the Office of the Chief Rabbi, and the London Beth Din. He was very instrumental in negotiating with those bodies to deposit here.’

A minute book belonging to the Board of Deputies dated 1844-1856 • Hidden Treasures/Jonathan Juniper

The first item Nicola showed us was a leatherbound subcommittee minutes book belonging to the Board of Deputies dated 1844-1856. ‘This volume gives such a good idea of the breadth of their work during that period,’ said Nicola as she carefully turned the immaculately preserved pages. ‘There are subcommittees in here for Jewish marriages, for burial grounds, for a memorial in Gibraltar, about a Jewish community in Turkey and even a letter to the Pope! Minutes like this are wonderful because they document how decisions were being made and reflect what was happening in Anglo-Jewy during that time.’

We examined another minute book, which documented a project by the Jewish Health Organisation, which helped the Jewish community to get proper access to health care and in the mid-twentieth century established a Child Guidance Clinic in East London. We explored some of the entries there, which were typewritten so easier to read. Nicola showed us a page that detailed the number of cases the Child Guidance Clinic had dealt with from January to June in 1936, and described the reasons children were referred to the clinic. Nervousness and excitability, pilfering, neurosis, unmanageable behaviour at school, nail biting, night terrors, apathy, dirt eating, insomnia and absent-mindedness were just some of the reasons listed.

From the next box she pulled out a thin blue pamphlet, celebrating the first 50 years of the North London Progressive Synagogue, which had been written by a member of the congregation called Millie Miller. She had been a member of Parliament and the Mayor of Stoke Newington and Camden. ‘We also hold Millie Miller’s personal archive so this pamphlet is a nice example of how a synagogue collection can connect with a personal collection,’ said Nicola.

Material from the Association of Jewish Teachers • Hidden Treasures/Jonathan Juniper

The next items were from the more recent past. Nicola explained that along with the larger and long-established Jewish organisations the London Archives also holds material from lesser-known societies such as the Association of Jewish Teachers, ‘which existed to support Jewish teachers, particularly those working in non-Jewish schools.’ Inside the file were photocopied reports published in the 1980s, homemade newsletters that told their own story of life for Jewish teachers in London during that moment in time.

Magazines from the Jewish Vegetarian Society • Hidden Treasures/Jonathan Juniper

Another more obscure collection they hold is a complete run of magazines 1966 to 2015 of the Jewish Vegetarian Society. ‘They are now digitised and available online through the Society’s own website, but the originals have come here for safekeeping,’ said Nicola.

The last two folders of material she showed us were very familiar to me. The first was from the former much loved Joseph’s bookstore in Temple Fortune, North West London, that had been deposited with The London Archives by the owner Michael Joseph when the bookshop closed in 2018 after twenty-five years of serving the community. ‘My mind was boggled by the amount of different things that Michael Joseph did at that shop,’ said Nicola as she looked through the flyers for book clubs, the café, the gallery, events, talks and musical concerts. ‘It was just amazing. This flyer is for a book by Sally Berkowicz ‘Under My Hat’ which was the first of two books that Joseph published under his own name. There is a flyer here for a Cup Final event, we have a full run of digital menus from the Cafe. It was such a well-known place and again there are so many connections and interactions with this collection and our wider Jewish collections from the late twentieth and twenty-first century.’

A photograph from the David Jacobs collection • Hidden Treasures/Jonathan Juniper

‘This last one to show you is from one of our individuals’ collections,’ said Nicola as she carefully extracted small, printed photographs of Jewish London from their folded acid free wrappings. The photographs had been taken by David Jacobs, an important British Jewish social historian who documented the remnants of the Jewish experience mainly in the East End during the 1970s and 80s when few others recognised the importance of this work. ‘From David we’ve got photographs, ephemera like newspaper cuttings, a lot of slides and photographic recordings of many Jewish buildings which no longer exist, before they were turned into something else or demolished completely.’

We spent some time exploring this wonderful collection, which included many images of a now vanished world in London’s former Jewish East End. ‘Our collecting remit is Greater London only,’ said Nicola, ‘but we are more than happy to talk to people and to find out what material they have. If there are Jewish organisations that would like to get in touch, and they’re based in London then we would love to hear from them.’

—Dr Rachel Lichtenstein