Collection Encounter: The Bible Room at Rylands

Our last ‘collections encounter’ at the Rylands was in the Bible Room, which is largely closed to the public, and for the last 120 years has stored the printed and handwritten bibles. Priceless leather-bound bibles from all over the world, from many different time periods, in languages as diverse as Armenian, Portuguese, Hebrew and Syrian lined large mahogany bookcases around the comparatively small square room. In one corner sat a low piece of dark wooden furniture called palki that resembled a small four-post bed, which is used during the visit of the Sikh community to display their sacred text. In the center of the room stood a large table, where four special treasures from the Rylands collections had been laid out in advance of our visit for us to explore.

Our last ‘collections encounter’ at the Rylands was in the Bible Room, which is largely closed to the public, and for the last 120 years has stored the printed and handwritten bibles. Priceless leather-bound bibles from all over the world, from many different time periods, in languages as diverse as Armenian, Portuguese, Hebrew and Syrian lined large mahogany bookcases around the comparatively small square room. In one corner sat a low piece of dark wooden furniture called palki that resembled a small four-post bed, which is used during the visit of the Sikh community to display their sacred text. In the center of the room stood a large table, where four special treasures from the Rylands collections had been laid out in advance of our visit for us to explore.

The first item we looked at was a tiny fragment of paper, a remnant of the folded pages of a handwritten manuscript (Gaster Genizah A281 & B5756). We bent down lower to inspect the Hebrew text on the tiny fragile remnant, which was pressed between two sheets of glass and resembled the shape of a butterfly’s wing. ‘This faded fragment it’s not just in anyone’s handwriting,’ said Zsófi smiling, ‘it’s in Maimonides’s handwriting!’ Moses Maimonides had been a famous Sephardic Jewish Torah scholar and one of the greatest philosophers of the Middle Ages. He was born in Spain in 1138, then worked as a rabbi, physician and philosopher in Morocco and Egypt, where he eventually became the head of the Jewish community.

The unknown autographic fragment we were looking at was a section of the Mishneh Torah (the code of Jewish religious law authored by Maimonides when he was living in Egypt) which had been found in the genizah of the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo and was now part of the Gaster collection at Rylands. ‘The Israeli scholar Malachi Beit-Arié identified the first fragment [who had sadly died the previous day],’ said Zsófi. ‘He was the father of Hebrew codicology, which is when you investigate the physical characteristics of a manuscript, and palaeography, which is the study of handwritten scripts. These can help with dating, and to establish the historical context of a certain book.’

It was hard to imagine that we would see anything more amazing than this extraordinary historic artefact, but every item Zsófi had selected for us was equally fascinating in its own way. Sat beside the fragment, resting on a cushion, was a fifteenth century Ashkenazi Passover Haggadah, which Zsófi told us had been produced in Southern Germany around 1430 (Hebrew MS 7).

The book was open on a particularly beautifully decorated page of the manuscript, which showed the main part of the Passover Haggadah text in Hebrew surrounded by colourful drawings bordered with an illustrated frieze, including depictions of foliage and a lion, a hare, and a monkey amongst other animals. ‘In most such illustrated manuscripts a typical portrayal would be of a family sitting around the table laid for the Seder feast but here you see something quite unique,’ said Zsófi with excitement as she pointed to a lady who appeared to be kneeling in the bottom right of the page wearing a long royal blue dress. Her resemblance to medieval depictions of the Virgin Mary from Christian texts was immediately clear. ‘Visually Mary was very important in the 15th century,’ said Zsófi. ‘In many Western manuscripts, you often see donors imitating her position because she was seen as the ideal pious woman. Ashkenazi Jews lived within a Christian community, so they shared to a certain degree the same visual language, so my argument is that they used the same visual language to depict a pious Jewish woman. And of course, this could also have a polemical edge challenging the superior position of the Virgin Mary.’

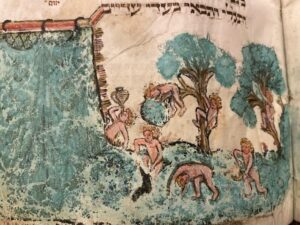

Zsófi told us the book was thought to have been produced by an Ashkenazi rabbi for his own personal use, so this lady was most probably based on a family member. She told us it had been usual in Jewish book culture of that period to have self-produced books, which was totally different to the big Christian workshops of that time where they produced manuscripts on a large scale. She showed us another unique page from this same Haggadah. ‘It’s the most fascinating iconography,’ said Zsófi as she showed us another illustrated page of Hebrew text, that appeared to show a group of frolicking babies climbing trees, swimming in a river, and drinking from an urn. ‘This is so unique. I’ve never seen it in any other manuscript,’ said Zsófi, as she pointed to the ‘wildlings’ playing and the large curtain that framed the scene on the bottom left-hand side of the picture. ‘This is an illustration of a midrashic story,’ she said. ‘This story explains how the Israelites could be so fruitful under Egyptian oppression. How? When their time has come, every Jewish woman went out to the fields to give birth without the Egyptians’ knowledge, and they gave birth to sextuplets. Then they went home leaving the babies in the field for the angel of God to took care of them. When the Egyptians came, God covered them with earth then uncovered them, and perhaps the curtain motif refers to this divine intervention.’

Zsófi told us the book was thought to have been produced by an Ashkenazi rabbi for his own personal use, so this lady was most probably based on a family member. She told us it had been usual in Jewish book culture of that period to have self-produced books, which was totally different to the big Christian workshops of that time where they produced manuscripts on a large scale. She showed us another unique page from this same Haggadah. ‘It’s the most fascinating iconography,’ said Zsófi as she showed us another illustrated page of Hebrew text, that appeared to show a group of frolicking babies climbing trees, swimming in a river, and drinking from an urn. ‘This is so unique. I’ve never seen it in any other manuscript,’ said Zsófi, as she pointed to the ‘wildlings’ playing and the large curtain that framed the scene on the bottom left-hand side of the picture. ‘This is an illustration of a midrashic story,’ she said. ‘This story explains how the Israelites could be so fruitful under Egyptian oppression. How? When their time has come, every Jewish woman went out to the fields to give birth without the Egyptians’ knowledge, and they gave birth to sextuplets. Then they went home leaving the babies in the field for the angel of God to took care of them. When the Egyptians came, God covered them with earth then uncovered them, and perhaps the curtain motif refers to this divine intervention.’

We moved around to the other side of the table to look at another very rare item from the Gaster collection, an eighteenth century Machzor (Gaster Miscellaneous MS 1596). A Machzor is a text that normally contains Hebrew prayers and liturgical poems both for everyday use and for special occasions, but what made this book so unique was that the entire text had been translated into English. ‘This manuscript was researched by Aaron Sterk, who believes that the English translation is based on a very early Spanish translation’ said Zsófi pointing to the sloping handwritten writing in black ink. ‘Because certain texts are missing from this version, he deducted that this had been produced for a female user,’ said Zsófi. ‘It is thought to date from about 1750 by the handwriting and layout. Apart from some texts used in the Reform and Progressive movements, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a prayer book which doesn’t have Hebrew in it. Aaron Sterk thought it probably had not been scribed by a Jew, because certain Hebrew word, like for example ‘Hanukkah’ are sometimes misspelled within.’

We moved around to the other side of the table to look at another very rare item from the Gaster collection, an eighteenth century Machzor (Gaster Miscellaneous MS 1596). A Machzor is a text that normally contains Hebrew prayers and liturgical poems both for everyday use and for special occasions, but what made this book so unique was that the entire text had been translated into English. ‘This manuscript was researched by Aaron Sterk, who believes that the English translation is based on a very early Spanish translation’ said Zsófi pointing to the sloping handwritten writing in black ink. ‘Because certain texts are missing from this version, he deducted that this had been produced for a female user,’ said Zsófi. ‘It is thought to date from about 1750 by the handwriting and layout. Apart from some texts used in the Reform and Progressive movements, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a prayer book which doesn’t have Hebrew in it. Aaron Sterk thought it probably had not been scribed by a Jew, because certain Hebrew word, like for example ‘Hanukkah’ are sometimes misspelled within.’

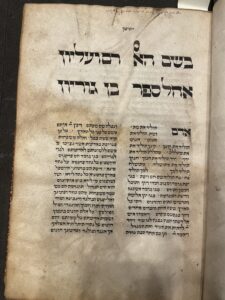

‘We have one more thing,’ said Zsófi with excitement. ‘An absolutely overwhelming treat.’ We moved around the table to the final item, a rare fifteenth century Italian printed Hebrew text, which on first appearance looked as if it had been handwritten by a scribe (17277). ‘This is a copy of the Sefer Josippon printed in Mantua by Abraham Conat, around 1475-80,’ said Zsófi. ‘He tells us that the book was printed the day before Shavuot, so 49 days after Pesach.’ What was so unique about this book was that the title at the beginning of the text had been handwritten, ‘You can even see the ruling’ said Zsófi, pointing to the faint pencil lines above the Hebrew letters of the titles. ‘But the main body of the text is printed! This is a great example of how these very early printed books imitated manuscripts because people were used to manuscripts.’

‘We have one more thing,’ said Zsófi with excitement. ‘An absolutely overwhelming treat.’ We moved around the table to the final item, a rare fifteenth century Italian printed Hebrew text, which on first appearance looked as if it had been handwritten by a scribe (17277). ‘This is a copy of the Sefer Josippon printed in Mantua by Abraham Conat, around 1475-80,’ said Zsófi. ‘He tells us that the book was printed the day before Shavuot, so 49 days after Pesach.’ What was so unique about this book was that the title at the beginning of the text had been handwritten, ‘You can even see the ruling’ said Zsófi, pointing to the faint pencil lines above the Hebrew letters of the titles. ‘But the main body of the text is printed! This is a great example of how these very early printed books imitated manuscripts because people were used to manuscripts.’

The first and the last parchment leaves of this printed book were covered with handwritten notes in Hebrew characters as well as in Italian. The notes themselves were fascinating, at times hardly legible, but Zsófi told us that they had identified the signatures of four Italian censors among them Domenico Irosolomitano, who was one of the most famous censors of the Italian Inquisition. ‘They employed mostly converts who could read Hebrew and check these Hebrew books to see whether there was anything anti-Christian in them. I have not found any erasures in this book but I recently saw a book which had the censorship notes and lots of deletions. Such a rich story. In the margins, literally!’ We left the Bible Room soon after amazed by our visit which revealed so many hidden stories both within the books, and of the books we had seen.

The first and the last parchment leaves of this printed book were covered with handwritten notes in Hebrew characters as well as in Italian. The notes themselves were fascinating, at times hardly legible, but Zsófi told us that they had identified the signatures of four Italian censors among them Domenico Irosolomitano, who was one of the most famous censors of the Italian Inquisition. ‘They employed mostly converts who could read Hebrew and check these Hebrew books to see whether there was anything anti-Christian in them. I have not found any erasures in this book but I recently saw a book which had the censorship notes and lots of deletions. Such a rich story. In the margins, literally!’ We left the Bible Room soon after amazed by our visit which revealed so many hidden stories both within the books, and of the books we had seen.

— Dr Rachel Lichetenstein